I know how to read!

Hi everyone! How’s it going? I thought I’d change things up a little bit this week and talk about what I’ve been reading recently.

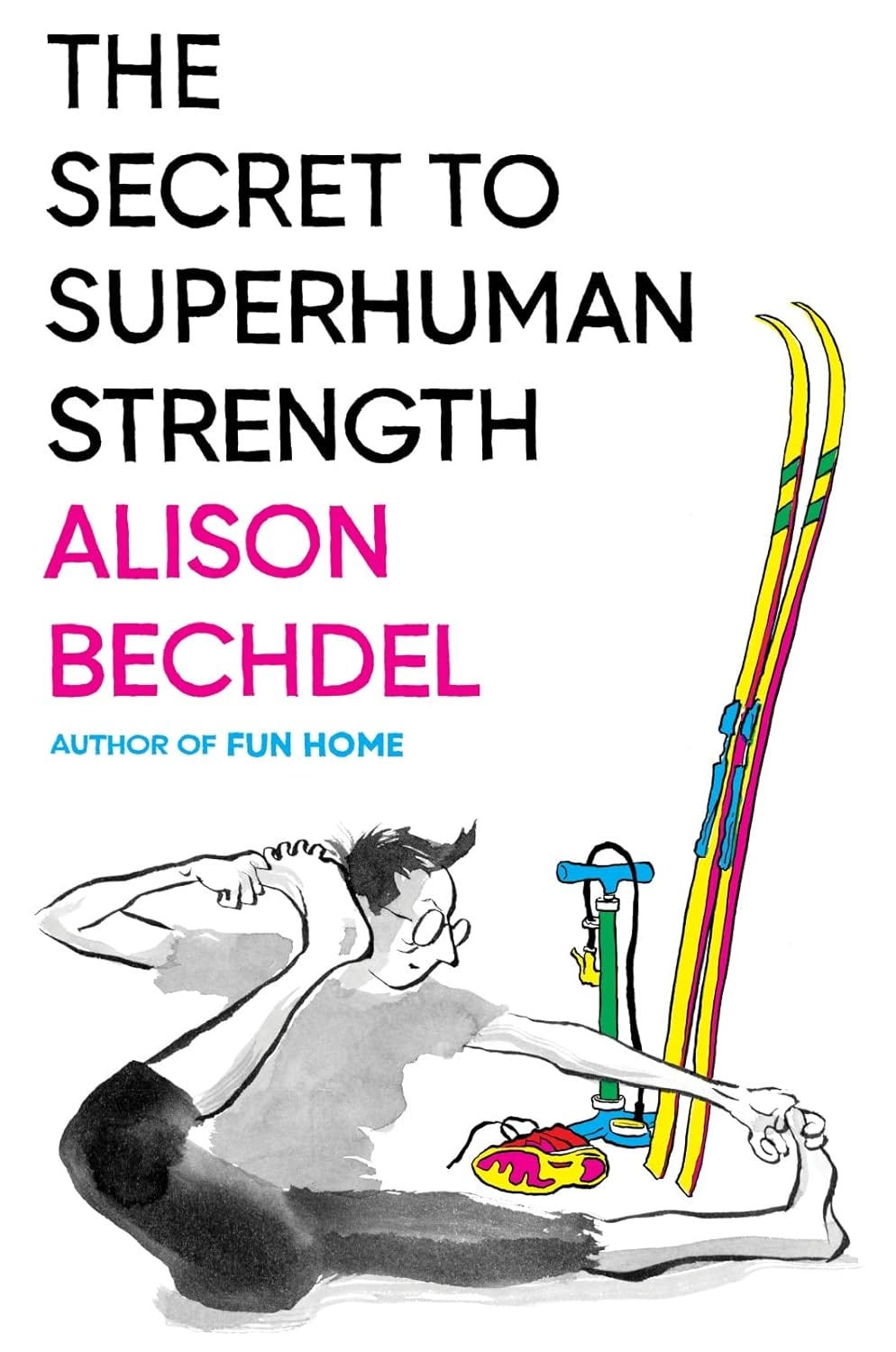

The Secret to Superhuman Strength

I recently stumbled on Alison Bechdel’s The Secret To Superhuman Strength while wandering through the library. You may have heard of Bechdel from the Bechdel test, which asks if a movie includes at least one conversation between two female characters about something other than a man.

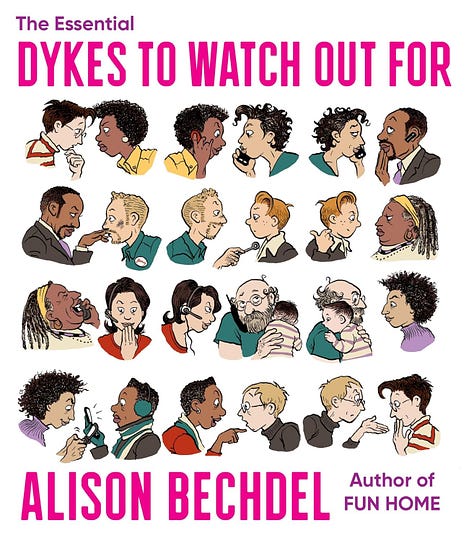

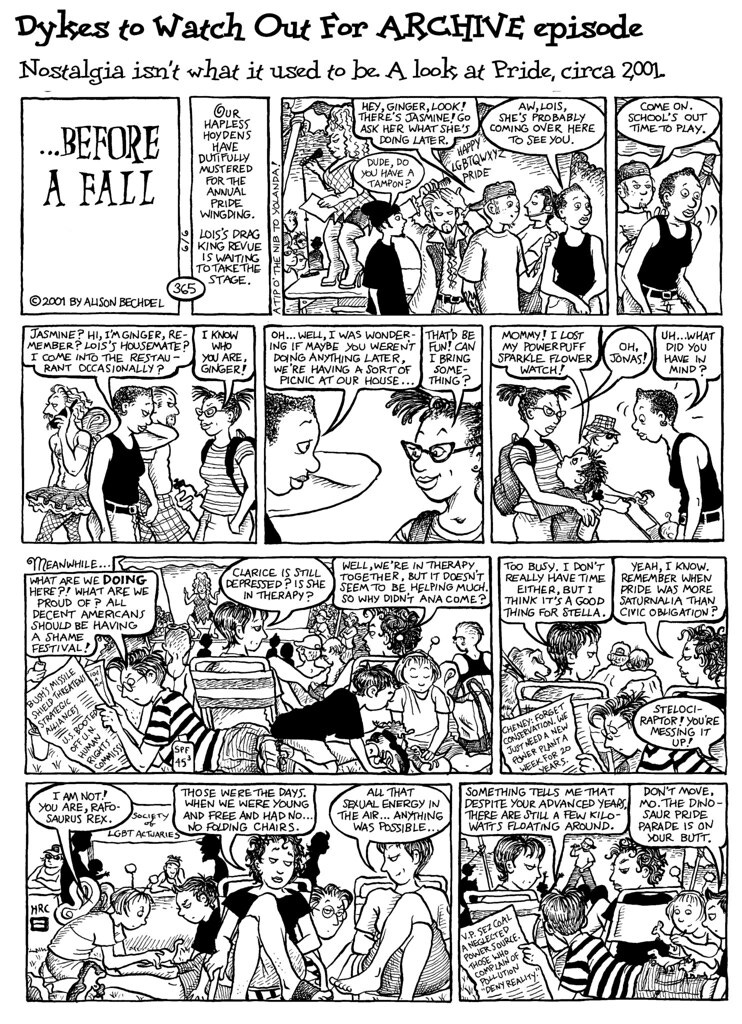

I first encountered Bechdel’s work some time in college, where I stumbled on a copy of The Essential Dykes To Watch Out For in the comics section of one of the St. Louis county libraries.

From Bechdel’s website:

My comic strip Dykes To Watch Out For has run serially in gay and lesbian newspapers since 1983. And over the years, a series of eleven collections have been published. These have contained all the newspaper strips, and have often also included a bonus “graphic novella,” or extended story about the characters.The first nine volumes were published by Firebrand Books, and the most recent two by Alyson Books. Though all the collections are technically still in print, they’ve gotten very difficult for readers to find, and for stores to stock.

This compilation seemed like a way to get Dykes to Watch Out For back onto bookstore shelves and into the hands of regular readers—and hopefully also into the hands of new readers who wouldn’t otherwise have run across it.

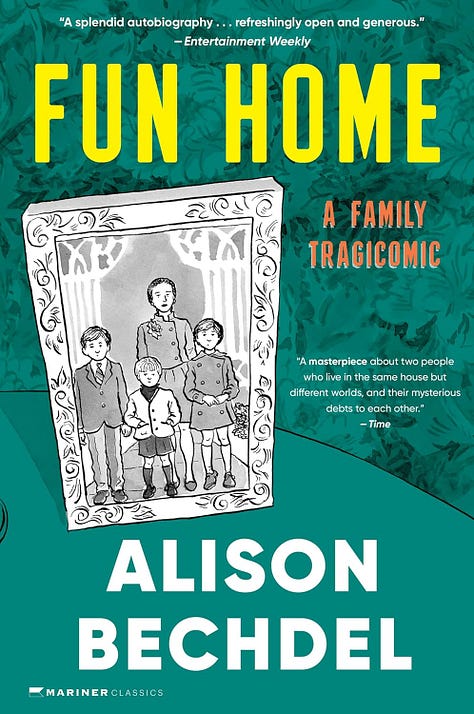

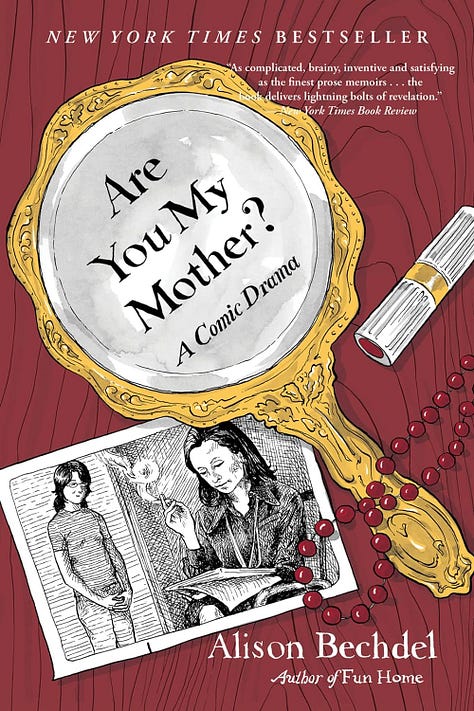

Like Fun Home and Are You My Mother?, The Secret to Superhuman Strength is graphic memoir, this time featuring beautiful water-coloring by Bechdel’s partner Holly Rae Taylor. I “read” the book in one sitting (I skipped the middle third), and immediately texted my friend Shan to discuss.

I’m very hesitant to “review” things, since most reviewers in my opinion forget that:

Anything gets published at all.

They might not fall within the intended audience of the work.

Just because you liked something doesn’t mean it’s “good,” and just because you disliked something doesn’t mean it’s “bad.”

That being said, you will probably enjoy TSSS if you enjoyed the page above, or any of Bechdel’s other works.

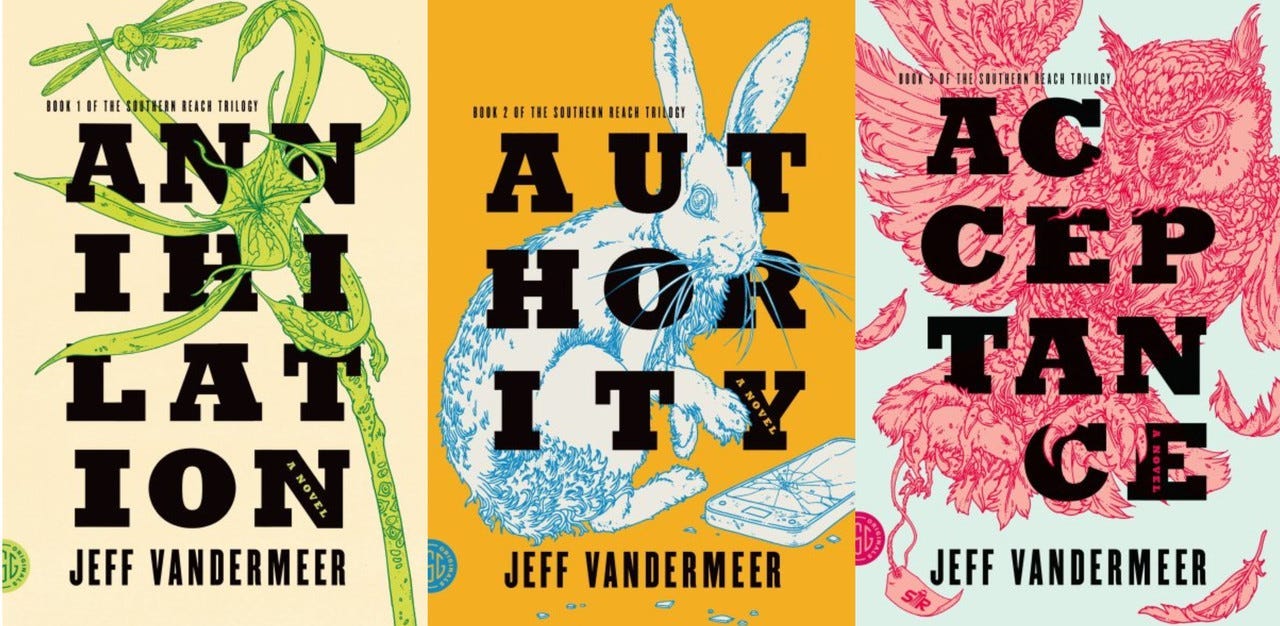

The Southern Reach Trilogy

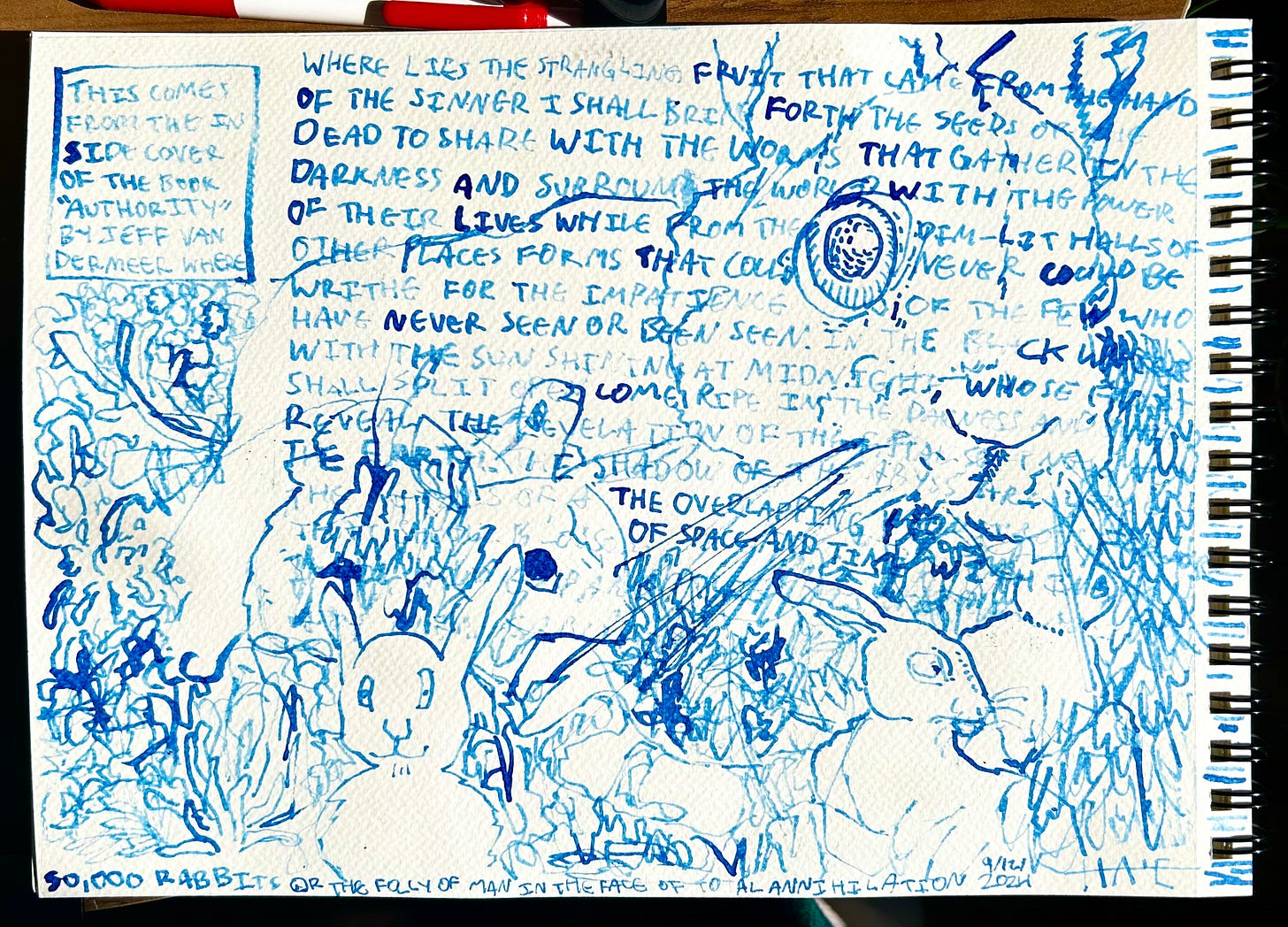

As I mentioned above, my favorite books are ones that grab you by the throat and demand you inhale them as quickly as possible. After five or six tries at the first paragraph, that exactly the feeling I got from Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation, a thrilling descent into eldritch ecology, psychological horror, [REDACTED], [SUPER REDACTED], and [EXTREMELY SUPER REDACTED].

Annihilation had been on my radar for several years, and like House of Leaves, I picked it up intending to adapt it for a tabletop experience without knowing anything other than the basic pitch. And let me tell you, this book is scary! Like, really scary! I got spooked by a jump scare of the freaking title! How the !@#$% did he do that?!

Probably my favorite part about Annihilation was its honest-to-goodness focus of ecology, rooted in VanderMeer’s countless hikes through some of Florida’s marshlands. I’ve heard many claims about stories with environmental details that “the setting itself is a character.” Often I’m frustrated by this argument because very rarely do authors from our colonial society treat the world as literally alive and having agency.1 But VanderMeer’s world is alive, and boy does it have agency.2

As I hurled myself into Annihilation’s sequel Authority, I started to see the outline of the adventure: Annihilation is kind of an open sandbox,3 with a variety of branching end states. The second sitting takes place in the tighter location of Authority, with characters grappling with the effects of the previous session through new characters. And Acceptance, well…4

Now is when I should say that Authority was way fucking scarier than the first book. And like, in the best way possible!

Winter’s Daughter

For several weeks now, I’ve been investigating the history of role-playing games to see what secrets I can uncover. It was about halfway through Authority that I stumbled on this video:

Ben Milton, the DM in this video and owner of the YouTube channel, is somewhat of an authority on the old-school style of roleplaying, also known as the Old School Renaissance or OSR.

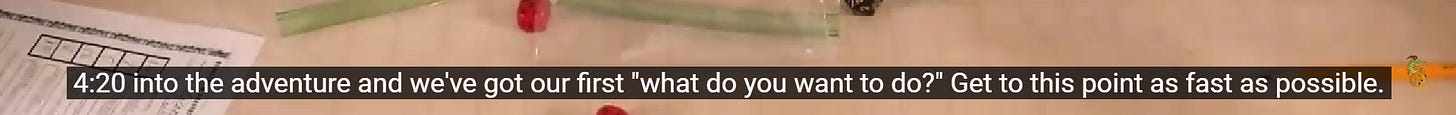

This video is kind of in opposition to many of the more famous examples of people playing D&D, where famous actors play out branded action sequences in the year’s most recent edition of the game. Instead, Milton takes the focus away from production value and puts it on the wisdom at play. Throughout the video, he uses the subtitles to provide commentary on the proceedings.

These two lines seemed eye-opening when I read them, but wouldn’t fully reveal themselves until they hit me like a truck while reading Authority: if role-playing games are about choice, then the basic unit of an adventure is not an event, as in a linear, Western story, but a decision nexus whose results can expand in any conceivable direction. This idea is hardly new, but it took me I guess a couple of years of reading OSR blogposts and such to understand it.

In other words: if the defining characteristic of role-playing games is that the characters in the story have complete agency, then the writing of role-playing scenarios should not necessarily try to anticipate what the characters will do, but instead provide them with many opportunities to make interesting decisions.

The Biopolitics of Root

I’ve also been looking into making games that accommodate 20 or even 200 players. It turns out that originally, D&D was an open-world tabletop MMORPG:

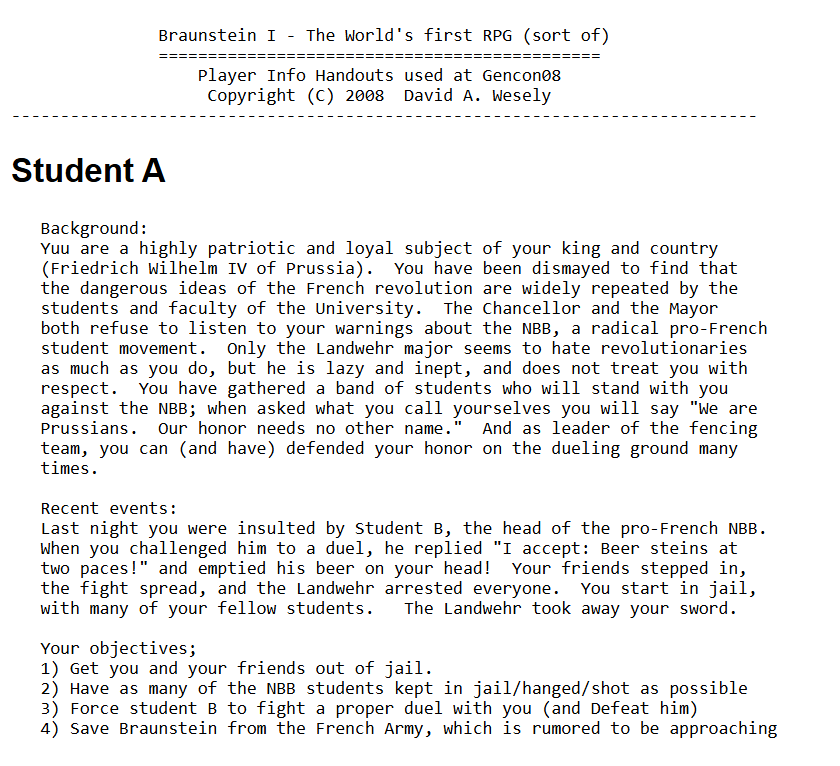

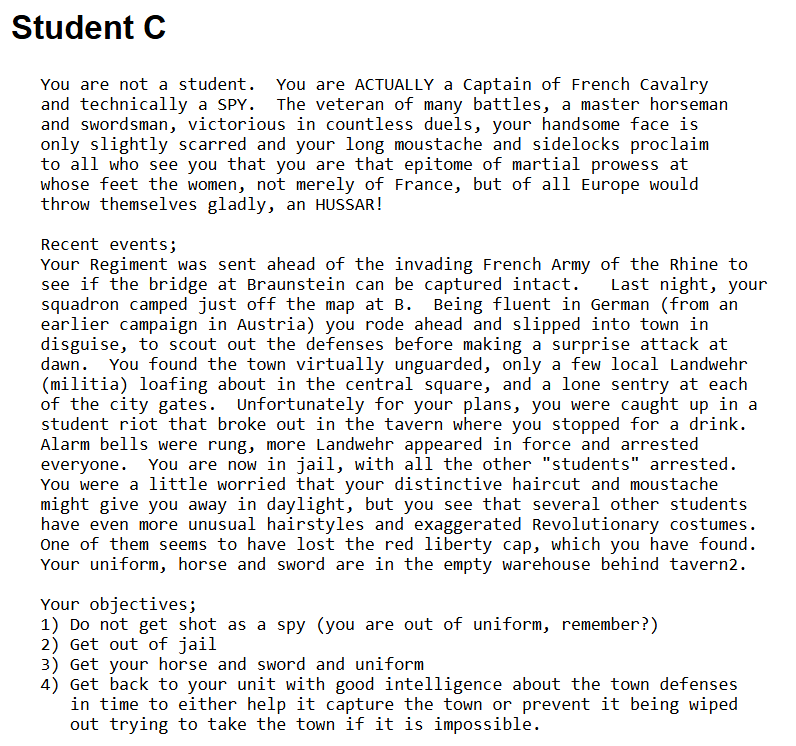

This line of inquiry led me to Braunstein by David Wesley, which is credited as the first example of American role-playing. Wesley gave each person a character sheet with background information and goals to accomplish, much like in a murder mystery party. Here’s one of the character sheets:

Wesley originally expected to referee all of the players’ interactions, but as more and more people started showing up, he started having to improvise new roles for the ten or so unplanned players. The accidental result of this was that while Wesley was preoccupied with giving the School Teacher motivations, the other players started talking to each other in character and pursuing their goals. In other words, the group accidentally invented what we think of as freeform role-play.

I am extremely interested in trying out this style of play, and extremely uninterested in playing Prussian students during the French Revolution. If only there was some other thing with a a bunch of competing factions and an interesting central tension…

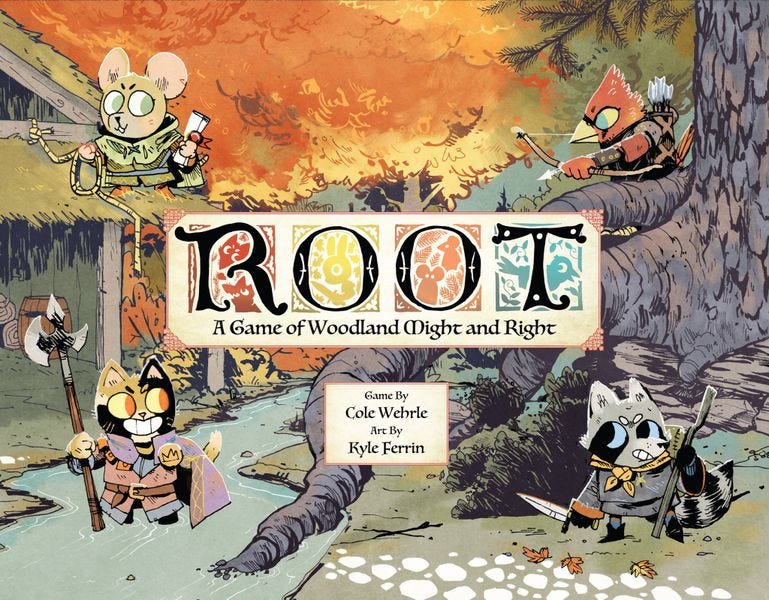

Root is a game that instantly drew me in through the artwork. But at the same time, the intensity of the wargame underneath felt repulsive. But why could I not stop thinking about it? WHY?

My initial attempt at answering this question led me to these blog posts, where the author analyzes the different factions of Root through the lens of Michel Foucalt’s theory of biopower. Biopower can be broken down into “life” and “power,” or power over life. The idea is that governments are very interested in controlling the different facets of people’s lives: how and what we eat, what kind of jobs we have, what we think, what entertainment we consume, what kind of people are desirable and get to reproduce, who gets to go to war, where we go to the bathroom, how often we wash our hair…

So initially I thought that Space Biff’s take was an interesting reading of Root, but it turns out that Root was directly designed as a game about biopower. If you’re interested, you can read about it on the designer’s blogposts about it.

Basically, Root is a game about governments competing to control the Woodlands. Each government has its own philosophy, its own vision for how the world should be. They express these philosophies through how they treat the civilians of the Woodlands, represented by cards in the game. Here are some examples:

The industrial Cats must spend civilians to produce more commodities from their factories.

The revolutionary Alliance must spend civilians to build sympathy for their cause.

The bureaucratic Birds must spend civilians to run their government.

I say “spend civilians” instead of “spend cards” because in the world of the game, each government must conscript citizens in order to advance their agendas. In other words, Root is a game about control over life, or biopower.

In essentially a defense of Root’s design, designer Cole Wherle talks about how our idea that games should be fair and have rules was actually an invention of the British Empire to colonize the minds of their subjects in India. I’m not kidding about this, and the talk is very interesting:

Therefore Root is not a “fair” game, and requires players to interact with each other as humans instead of a collection of plastic pieces. And while all of the factions in Root fall into archetypes we might recognize, none of them have specific political or moral philosophies about our real world. In other words, Root does not have an explicit intended political message as a rejection of colonial thought. Let’s hear from Wherle himself:

With the other factions, I did my best to avoid coding each with a specific ideology. This is was partly because of my own position that ideology ultimately grows after material or geopolitical circumstance. (I'll stop myself here from going into a very very very long embedded essay about why that is and what precisely I mean by that statement.) Suffice to say, you can play the Alliance as Marxists or Anarchists or or small “r” republicans. They could be extreme or moderate in position. Players were welcome to project their own political feelings on to any faction.

But this still begs the question for me:

Of course, I would normally be very excited about an anticolonial board game. As my friend John Crane Madden IV put it:

“What? There are board games about something other than colonialism?”

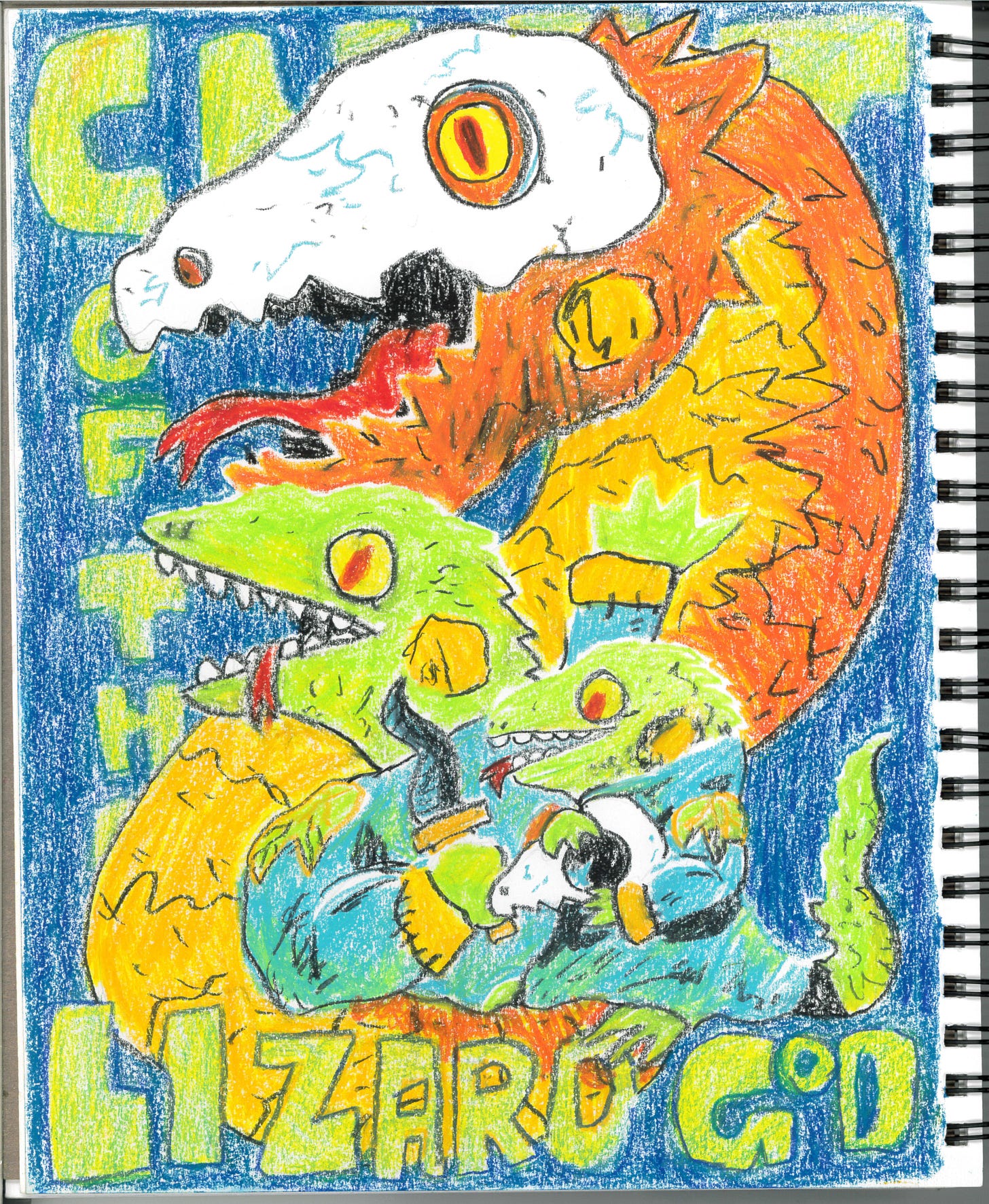

But it strikes me as very weird that Root seemingly rejects colonialism through industrialization, aristocratic dynasties, astroturf revolutionaries, lizard cults, and messiah figures. In other words, if we think colonialism is evil because of the way it treats civilians, why are we refuting it through a framework that also abuses citizens? And if game rules promote the philosophy of law and order, why is Root so mechanically complicated?

Furthermore, why has like the entire design team said that Root’s art was crafted to make the pills of war more palatable for non-wargamers?

Why does a game supposedly opposed to colonialism pretend to have nothing to say?

It’s become kind of a joke among my board gamer friends that I tend to dislike all of the “popular” games, including Root. I think a large part of this is my despair that so much of our art form is dedicated to replicating such vile parts of our history and economy. JCM IV is far from the only one to enjoy a colonialism simulator; Root, like the best of them, is meant to be fun.

I think the simplest answer to all of my questions5 is that Root is a commodity created to generate profit, and you can’t buy your employees health insurance by making a game about how empire is bad and communism is good.

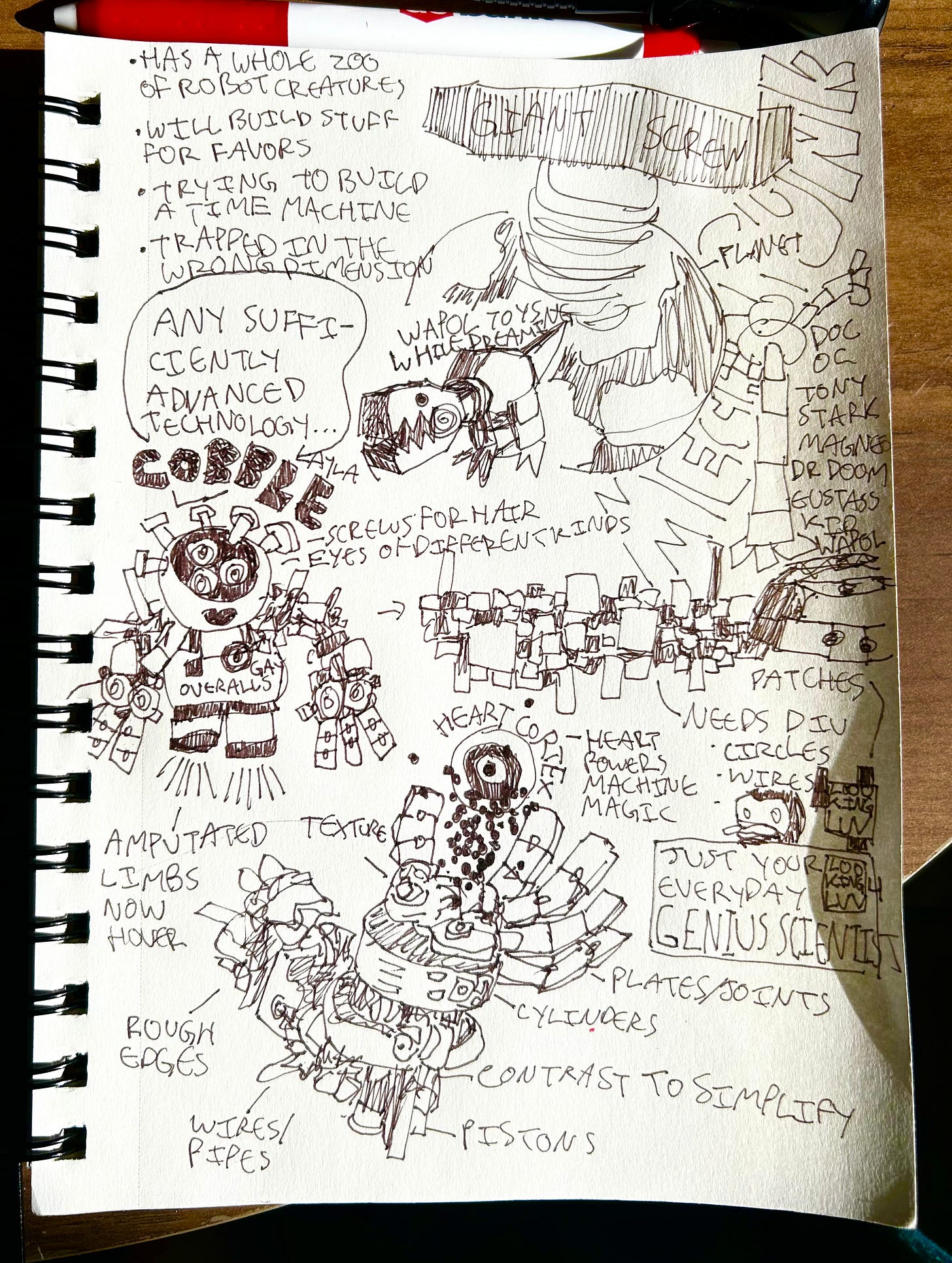

An attempt at a solution

All of that to say: I’m thinking about writing a Braunstein-like scenario that takes place in one of the factories of Root’s Woodlands. Some of the players will be the Cat running the factory or an Alliance member trying to overthrow the Cat’s regime. But most of the players will be the Small Folk, the mice, rabbits, and songbirds who make up the Woodland’s working class. Like Wherle’s use of the cards in Root, my hope is to make the military factions actually need and gain the support of the world’s everyday people. Is it as good as the Communist Manifesto? Probably not. Will it be fun? Maybe. Will it be interesting, 10-20 people simulating the politics of the Woodlands? Certainly.

BONUS MANGA

This is maybe a spoiler but one of my favorite books by N. K. Jemisin is also a notable exception to this trend. Maybe I’ll reread it sometime soon so I can write about it.

It’s probably a fair criticism that Annihilation’s wilderness implicitly espouses our colonial idea of a “pristine” wilderness that in being free of humans erases the indigenous populations. I guess you could also argue that the pristine in Annihilation is alien and signals the end of the world, so… I’m not really sure. Someone smarter than me can deliver a verdict on this.

This part is probably going to descend into game design nonsense that will almost certainly be incomprehensible if you haven’t read the books. I’m hoping to protect my future players from spoilers, but feel free to yell at me if none of this makes sense. I might already be contaminated by Area X.

I haven’t read it yet. But don’t tell anyone.

I have to say that I really do feel cowardly for writing this without asking Wherle himself what went into Root’s design philosophy. Maybe I’ll get to do that someday.