What do you learn the second time around?

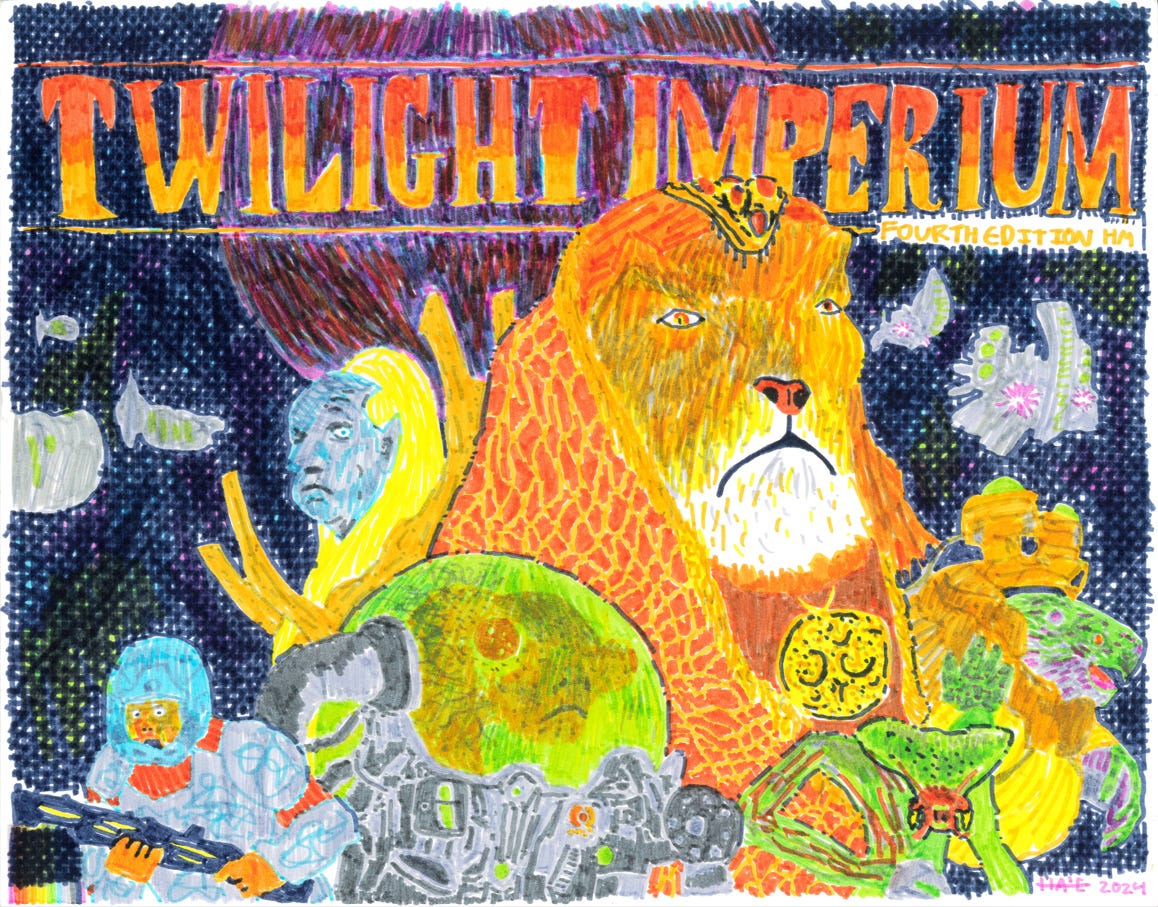

This week, we returned to the realm of the Lazax for another 14.75-hour game of Twilight Imperium 4th—

A couple of weeks ago, I called TI one of the best games this side of Mecatol Rex. But did it hold up to my praise after the veneer of novelty had worn off?

Between playing Root, TI, and other competitive games, I’ve been thinking a lot about how fun a game is for the losers. Of course, your answer to this question will depend on what you think is fun. But I’m going to tell you why I’m still thinking about losing a fourteen-hour game a week later.

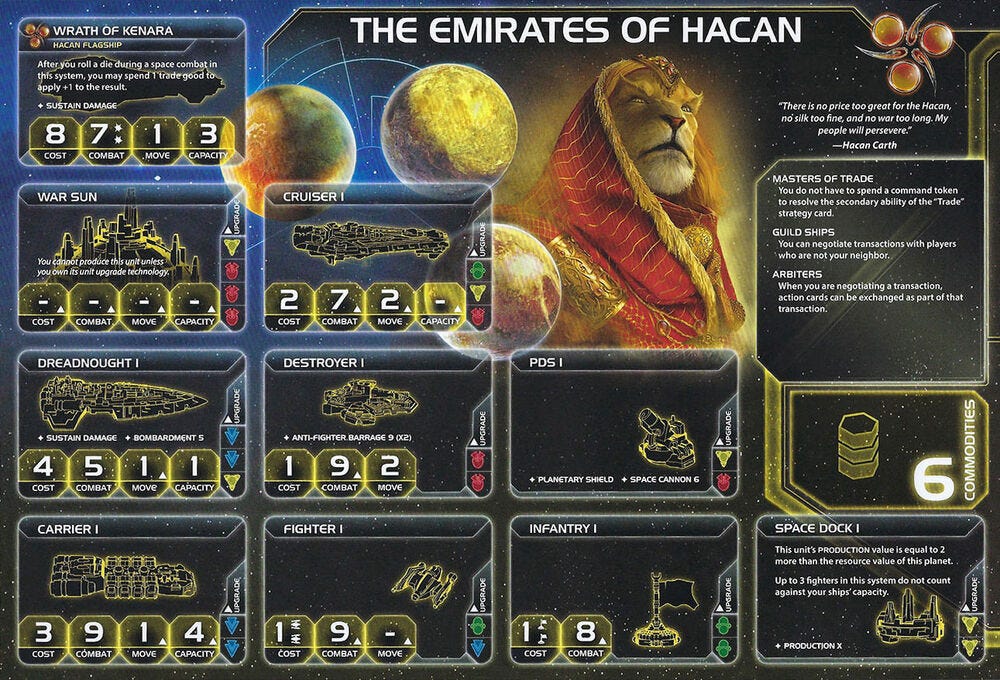

This time around, I played as the Emirates of Hacan, a somewhat orientalist conglomerate of space lions who specialize in making commodities and paying everyone else not to nuke them.

What differentiates the economy in TI4 from other games is that in order to turn your stuff into money, you need to trade it with other players. This means that, in addition to making the most money, the Hacan also specialize in diplomatic relations with other players. Last time, I described this as an “invisible political dimension that hovers over the board.” And yes, I’m quoting myself. Because it’s cool and true.

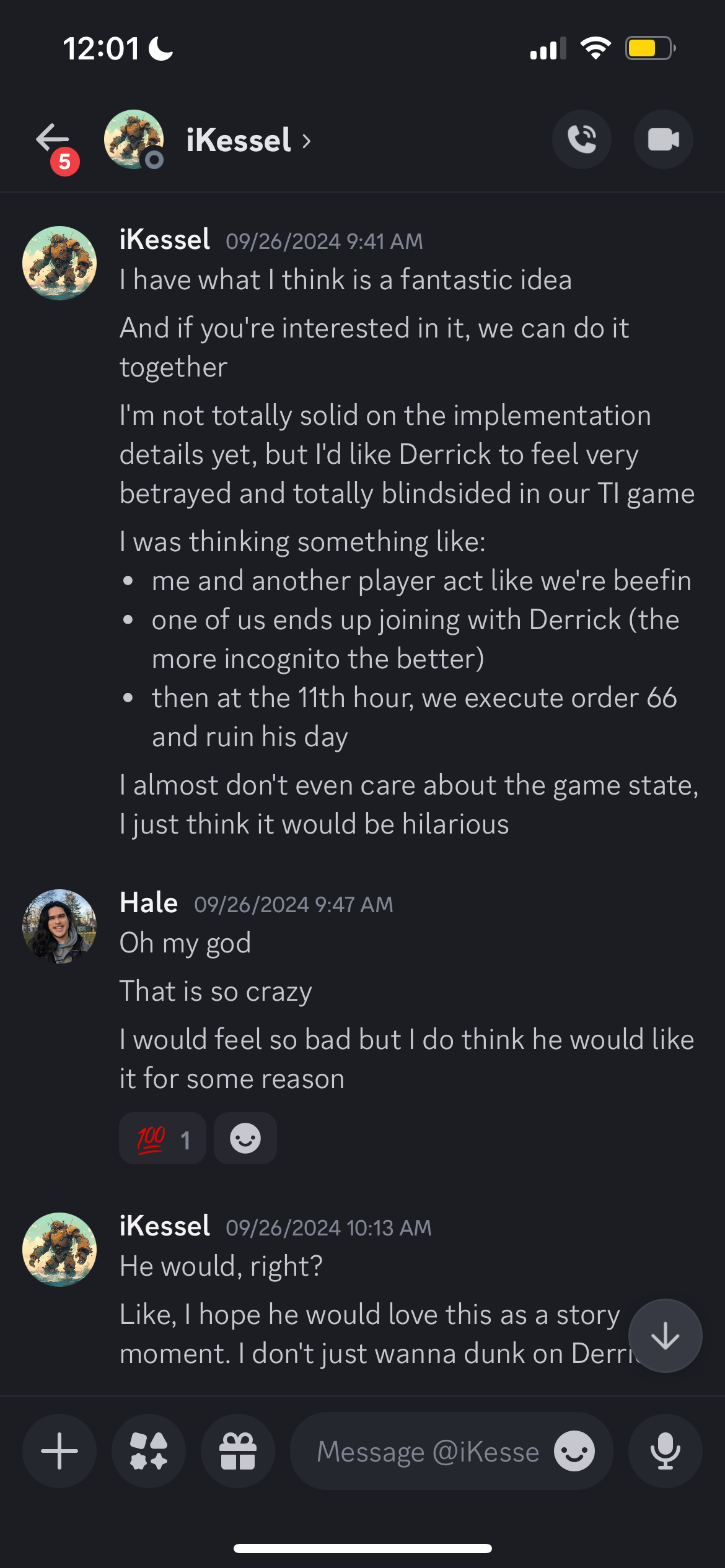

We had fewer players this time around, and everyone already knew the game. But our negotiations were so intense that the game took just as long. Bargaining for territory. Debating resolutions. Negotiating alliances. Breaking treaties. Say what you will about space colonialism, there are very few games that center so forcefully on real politik.

And something interesting happened. For someone who is generally opposed to games about war and conquest, I was really good at the politicking. I almost went the entire game without getting punched in the face. Almost.

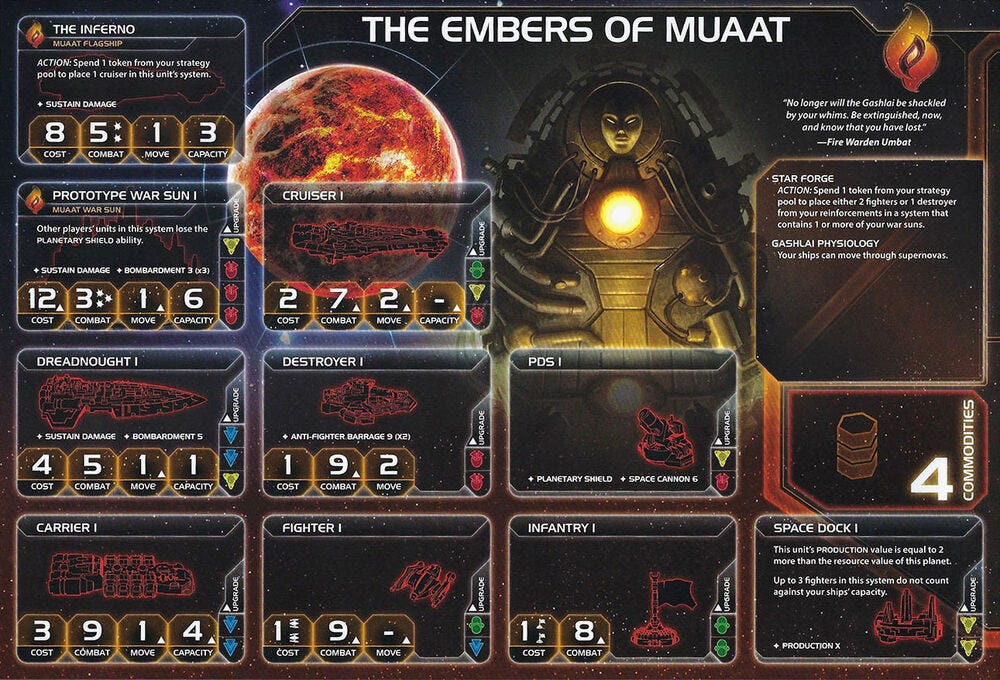

I had just spent the past twelve hours methodically playing each of my enemies against each other, funding all of their militaries as long as they promised not to attack mine. I even negotiated an end to democracy in the legislative phase, even though my side had dramatically fewer votes! But in the thirteenth hour, the neighboring Embers of Muaat turned the center of my fleet into a supernova. My chances of winning dropped to zero.

Are you willing to suffer utter humiliation? Are you ready to see hours of hard work blown into a million pieces? Do you have the willpower to find a glimpse of hope in the void of despair? These are the questions TI asked of me. For it is only from the depths of desolation that we have seen anyone rise to victory.

Around the tenth hour, Chris said to me, “You’re playing really well man. I think you have a much better understanding of when to be friends with people, and when to betray them.” It was at this moment that I lost the game. I do not know when to betray, and I probably never will.

The noose is always tightening: as the game goes on, those neighbors who were such crucial allies in the beginning of the game are now your biggest, closest obstacles to victory. In other words, the game asks: will you turn your friends into an opportunity? I think we see games of strategy as politically/emotionally neutral. But planning is not enough to win a game of TI4. The winner of Mecatol Rex must lie, betray, and bully their way to victory. And not everyone is a person who wants to lie, betray, and bully.

And yet, what am I thinking about a week later? It’s when my ass got blown up and turned into a supernova. I think what has set TI apart from other titles for me is that the experience expands so broadly beyond what comes in the box. Even if the strategy wasn’t so interesting, the social element would be enough to hook me. And even if the social element wasn’t as engaging, it’s hard to sit next to someone for over twelve hours and not become friends. I guess what I’m saying is that despite the bloodthirsty betrayals, TI is about more than just winning in a way that most games are not. And that’s pretty cool.

By the way, Chris’ secret to winning is to get pummeled in the early game, and lag behind in the midgame. Then, when everyone is busy killing each other, quietly score your last 4 points in round 4 or 5 for the win. But don’t tell him I told you.

Part IV: And What If You Lose?

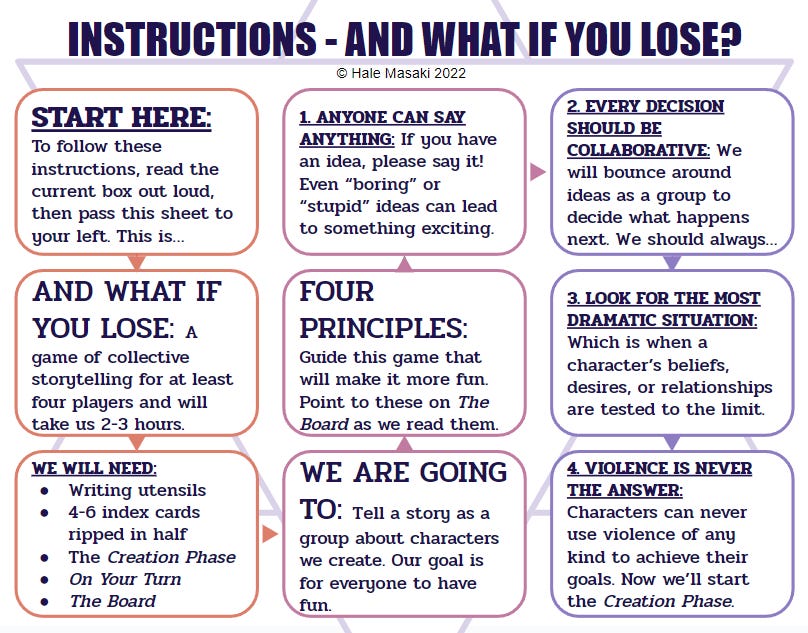

This is the fourth part of a series recounting my descent into the world of role-playing games. For anti-war propaganda, see Part I. For an introduction to independent RPGs, see Part II. And for a literature review from the pits of despair, see Part III. This is Part IV, which will focus on my prototype AND WHAT IF YOU LOSE?

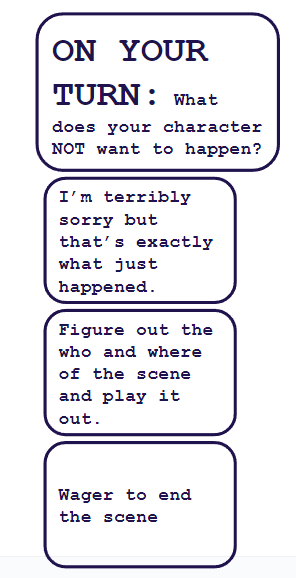

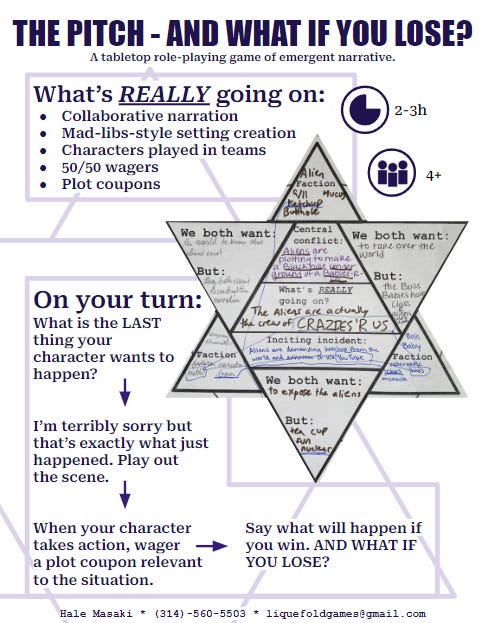

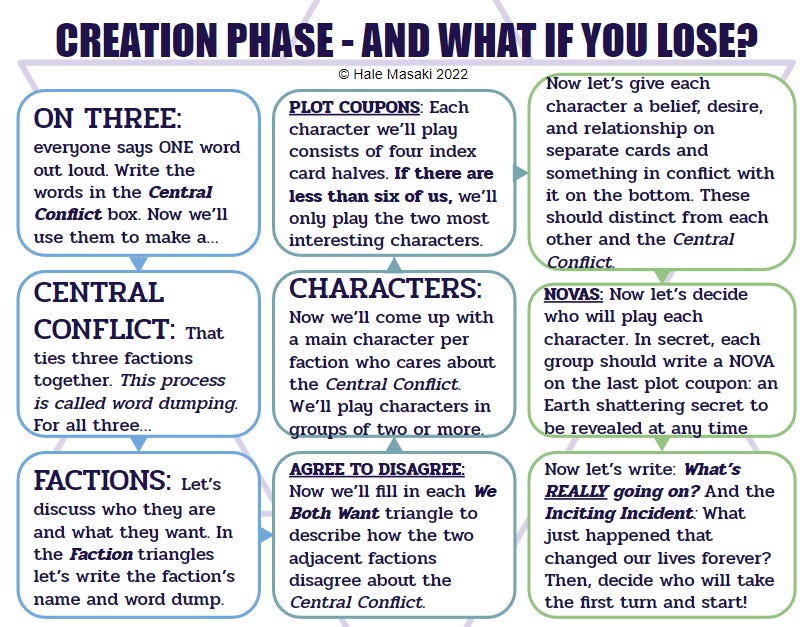

In AWIYL, the group creates three factions in conflict with each other. Then, players get into groups of at least two to pilot characters from the different factions. Here were some of my notes before the 7/7/2022 playtest:

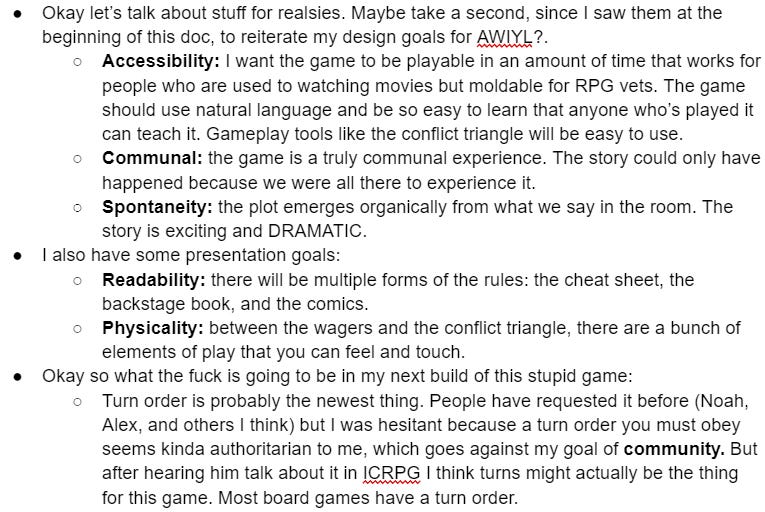

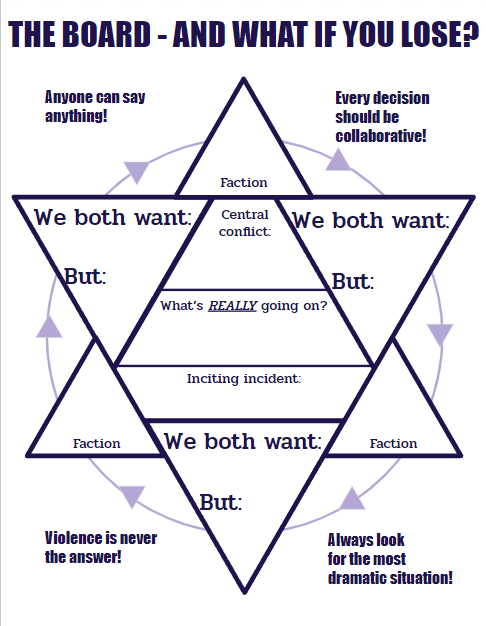

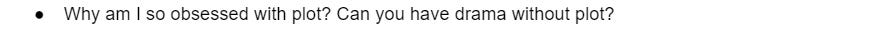

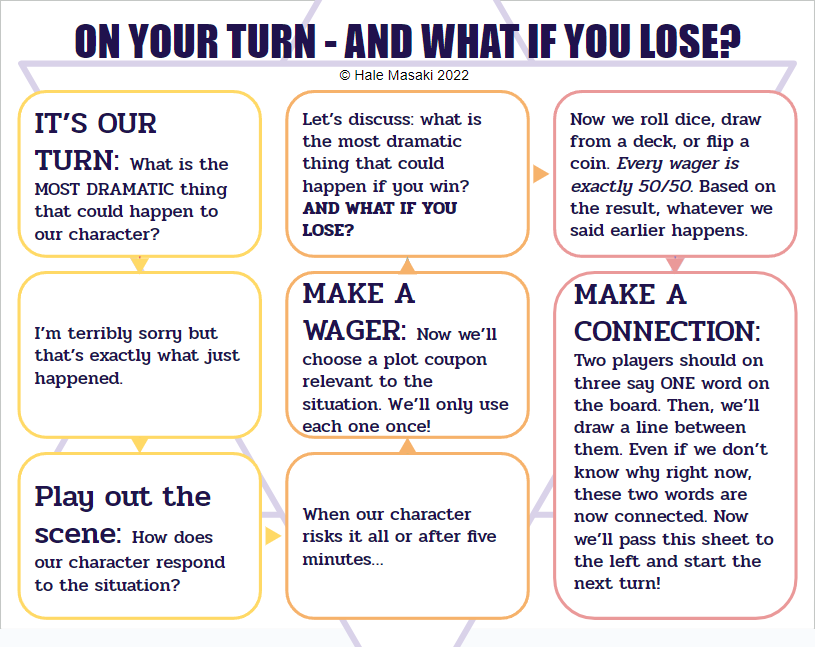

What exactly does a turn look like? Here’s part of the visual aid I made from this era of the game:

One of my main complaints in Part I was that most traditional RPGs do very little to tell whoever is running the game how to decide what happens next. My first solution to this problem is above, to ask the group: what is the most dramatic thing possible that could happen to this character right now?

Players then respond by wagering a related plot coupon, with each wager being a 50/50 chance. The players say what happens in the story if they win, and what happens if they…

lose, in addition to ripping up their relevant plot coupon and losing it forever.

In addition to the wagers from Never Tell Me The Odds, the DM-less paradigm from Dream Askew, and the turn structure from Index Card RPG (see my discussion from last week), AWIYL has some of my own (and as far as I know, unique) additions:

Each character is controlled by at least two people.

The board is also somewhat part of each character sheet.

There’s no session zero, pre-packaged setting, or prep.

This version of the game was… fine most of the time. Here are some of my notes after having 5-10 playtests under my belt:

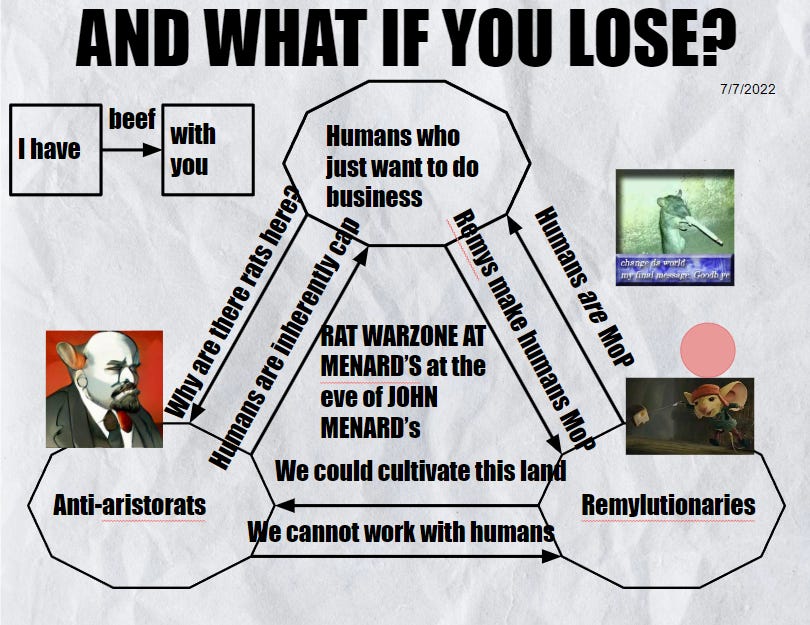

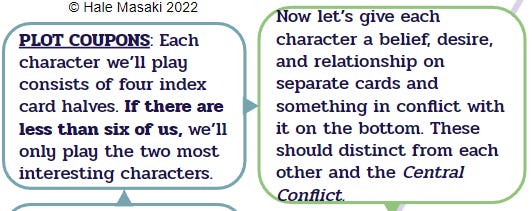

Around this time, the game looked like the picture below. And no, it’s not propaganda. It just so happens that I like triangles more than three-way Venn diagrams. And also that I like propaganda.

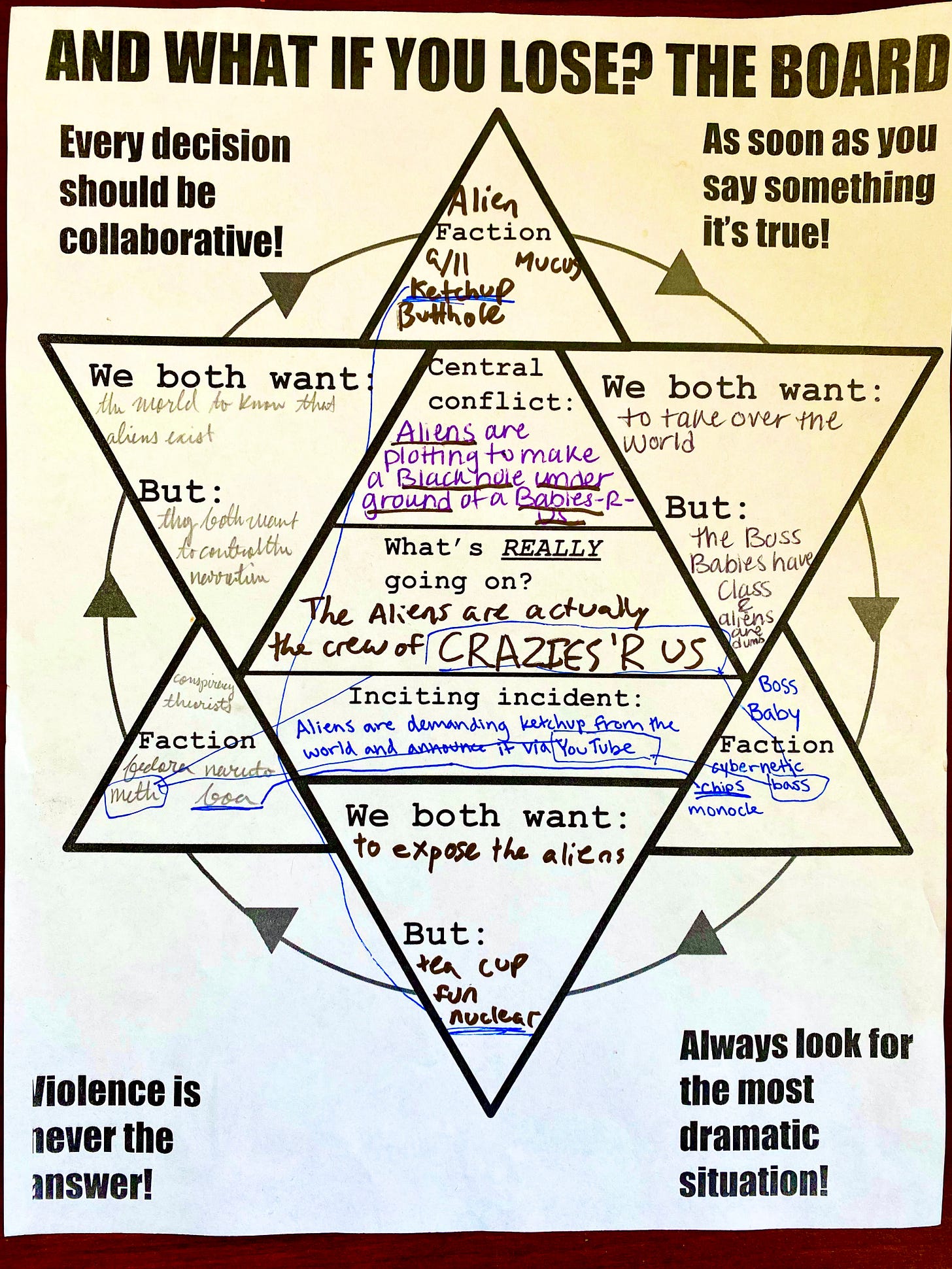

Now is probably when I should say that AWIYL is pretty weird. I don’t think there’s anything on the market quite like it. Here’s what a board looks like filled in:

There were certainly moments where AWIYL was exciting and funny. But was it fun every time? The more I tested, I found that setup, narration, and the guiding principles took too much brainpower for the average non-improver. The prohibition on violence was especially tough. Caught between my desires to follow the fun on one side and uphold my political commitments on the other, I was slowly stretching into madness…

A map?

Worldbuilding?

Expanding character creation?

We’ll answer those questions next time in Part V: Cartoodle. But before we say goodbye, I should probably tell you about the last playtest of AWIYL.

I had always known that AWIYL, using 50/50 coin flips to decide major plot points, was fairly swingy. There were ecstatic highs and soul-crushing lows, but always the two together. As long as we have some wins, everything should be fine. I mean, statistically, it’s never going to happen that we’re going to lose six coin flips in a row, right? Right?

In the last playtest of AWIYL, we had someone who had the highest affinity for doom of anyone I have ever met. So not only was each situation more dramatic than I could have possibly imagined, we lost every damn coin flip. Was it dramatic? Yes. Did it feel real? Certainly. But was it fun?

Let’s just say I learned a lesson about the importance of logical conclusions. Next week, we’ll see where I was headed with maps and expanding character creation.

BONUS MANGA

I promised bonus bonus manga, and I shall deliver. Exhibit A: A pitch doc.

Exhibit B: The final rules.

Feel free to reach out if you want a PDF of AWIYL to play. It’ll certainly be an interesting experience.

throwback to shrek/barbie reveal in the treehouse